ATC - Online Headaches?

Introduction

Moving to an online environment can be good fun but it can also expose crucial gaps in your knowledge. Coming face to face with ATC, controlled airspace and IFR flying procedures is rewarding when it goes well but can be awful if things begin to unravel. Oddly enough it isn't entirely your fault - it is partly the way in which FS leads you into these deeper waters but has avoided exposing you to the real complexities of IFR flight.

This article covers some of my thoughts about why FS can leave you unprepared.

Please note that the following article covers a very in depth look at real pilot workload and some detail about how pilots interact with ATC. I do not suggest that every FS pilot should try to adopt the following guidelines when online. The article is mostly for those pilots wishing to follow real world IFR procedures as accurately as possible and where the traps lie in doing this. For other pilots I hope it may just provide some interesting background.

Why did it all go wrong?

The basic problem is that FS users tend (and are encouraged) to jump in the deep end.

Take one moment to ponder.

A real pilot spends years in developing skills that end with him sitting in a big jet and able to fly into any major airport round the world. Part of that development is a good slice of ground examinations, simulation training and lots of book reading. Slowly (sometimes painfully) accrued knowledge over time.

FS users don't have that mass of background learning. We all pick a bit up here and there and think we have a good amount of knowledge under our belts (that's actually true) but it is a fraction of what a real world pilot knows. This is why things tend to unravel when you start flying in a more complex and real time environment. When you hit a problem there's no time to ask questions or look the books up.

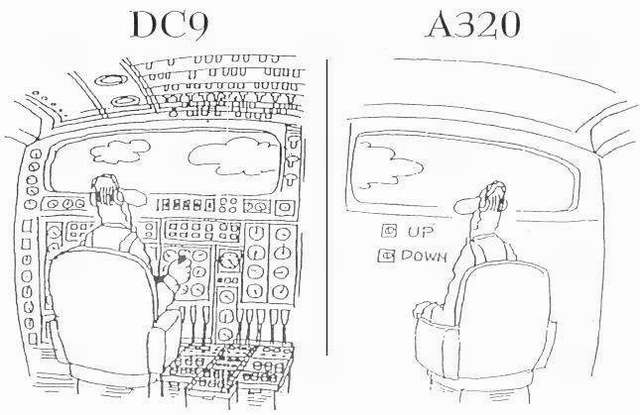

Once you get the hang of an aircraft and its automatics in FS it can be fun flying round the world but (be honest here) your skill set is rather limited. For most flights it is a matter of banging in the autopilot just after take off and then letting the aircraft fly the route entered into FSNav or the FS planner. On arrival you will either choose a runway nominated by ATC or plan your own in FSNav and let it do its thing, namely to put you in a sensible position from which you can pick up the ILS. You all do this - and so do I - because that is the way FS lets you.

This isn't a bad thing up to this point as you still learn a lot and gain much needed skills - and pick up some real knowledge along the way. However when you jump into a live ATC environment it can still come as a shock.

Why is it a shock?

1. Because in FS you get led into a mindset of planning a flight and then flying that plan.

2. Because in a live situation things change and your planning can go to pot even before you taxi.

It can be fun planning a flight in FS and then flying it to perfection but in reality this rarely happens. The same applies to online flying in that events triggered by other aircraft, weather or ATC can have the planned flight go out of the window before you get off the ground. That doesn't mean you don't plan a flight - that bit is still essential - but it means you have to develop adaptability to cope with changing conditions. This is what the FS planning system doesn't teach you.

Real world flying is highly flexible!

The answer to the problem is not so much in going back to the books but in changing your thinking processes. You need to develop some flexibility to cope with the unexpected.

Let me use a simple example of actual airline flying to explain this. I'll describe a typical airline flight below but intersperse this with comments relative to FS flying and with more detailed remarks on systems or procedures that are likely to be unfamiliar to you - but which you really ought to know.

Planning stage

A real world airline pilot wants to fly from Ronaldsway to Heathrow. He doesn't file a flight plan because these are now automated and submitted to ATC by the airline operations en block for summer or winter seasons.

The route BA used to file was DCT KELLY L10 WAL BNN3A. No problem there as the plan will also have been input by the airline ops into the aircraft's FMS ready to be called up. Note at this initial stage that the flight plan data doesn't take into account the departure or arrival segments for the airport.

The pilot will check his Met forecasts and will make a fairly good guess as to the runways likely to be used for departure and arrival. However this is not going to be any more than a guess at this stage. More important aspects of the Met briefing are take off and landing conditions (especially if visibility is close to published minima) and any en route weather that may affect the flight profile - thunderstorm avoidance mainly the culprit in the UK.

The pilot will also check NOTAMS and Bulletins to make sure there are no restrictions or problems for the planned route and destination. If there are (rare but it happens) it may require the standard route in the FMS to be ignored and a new route to be calculated.

Cockpit

Once in the cockpit and amid all the aircraft system checks he will tune into the ATIS (or call ATC) and will find out the departure runway. At Ronaldsway with no SID procedures this isn't critical for setting up the FMS as the pilot will expect to simply climb out on nominated runway heading to about 1500ft and then turn on course for KELLY. However another duty to be carried out is to look up the runway details and calculate the take off values - engine settings, V1, VR and V2 - and set these on the placard in the cockpit.

For an airfield with SID's the pilot can go one further and dial up the appropriate SID for that runway into the FMS - or get the plates out if the aircraft isn't that posh. Regardless of doing this the crew will have all the airfield SID's handy (Aerad's or Jepps) so they have instant reference to them - in case of change.

Start Up

Once the aircraft has started and is ready to taxi ATC will direct it to the runway in use.

TRAP 1 - This can be ANY runway.

The traffic situation, weather, accident, maintenance or a runaway horse (it's happened) may easily cause a change of departure runway and so you must treat the original ATC/ATIS data as a guideline only. In other words you can't really be certain of your departure runway and initial outbound route until you call ATC for taxi.

RULE 1 - Be prepared for a departure off ANY runway. This means a rapid rethink on departure procedures, recalculation of take off speeds and maybe reprogramming the FMS.

At a SID airport a runway change would involve reprogramming the FMS with the SID for the new runway (or getting the correct plate out of the manual) and the recalculation of the take off figures for the placard. In the real world most crews would do this as they taxi out to the runway but this is a benefit of having two crew..

In FS you are on your own and it is darn hard to taxi out without this extra workload to deal with. You already have compound tasks to handle - finding the right taxiway route, talking to ATC and going through a basic checklist. Don't add to this.

Solution. Tell ATC you will be taxying in three minutes (its polite - he may be holding another aircraft for you) and relax while you adjust your plan/FMS for the new runway.

At Ronaldsway workload can be compounded. If 08 is offered when ATIS originally gave 26 as the duty runway then the crew only have a few hundred yards to taxi to the hold! They have to work fast to recalculate the take off speeds (08 is a bit shorter than 26 and with many aircraft now programmed for reduced power take offs runway length will dictate the power required which can affect the V speeds) - but clever chaps without an FMS would have done this exercise in advance. The FMS isn't really an issue regarding runway changes because KELLY is still the initial aiming point and regardless of take off direction it will pick this up on departure.

Again, as at Heathrow, FS pilots should delay taxi if you need time to absorb the change and make adjustments. The trick here is to know your aircraft systems and be aware if a runway change requires any reprogramming. It isn't critical for GA aircraft but it may be quite significant on turboprops or jets with more complex flight management systems. If you have these get to know them very well.

Clearances

A slight divergence here but since we are covering an actual flight it is worth mentioning.

At major airports with SID's your flight profile is already fixed and you'll exit the SID already injected into the airway. In this case the airport only has to advise airways that you are on the move - no co-ordination is required.

At non SID airfields like Ronaldsway ATC have to contact the Centre Controller to get a clearance into the airways system. This is done when you call for taxi.

The result is a difference in procedures for the departing aircraft:

1. At an airfield with SID's you ask for, and get, your clearance before start up. This is a simple transmission comprising of the SID itself and a squawk.

2. At a non SID airfield you can expect to get your clearance only after you have started to taxi. This is because ATC ring the Centre as you call for taxi and speak to the Centre Controller to negotiate a suitable level (and maybe a heading) to get the aircraft slotted into the traffic already on the airway. The clearance will be verbose - at the briefest it will be "JHB999 is cleared from EGNS to EGLL via L10, maintain FL230, squawk 5415" but other traffic may result in further limitations in the clearance. An example - "JHB999 is cleared from EGNS to EGLL via L10, climb to FL90 expect further climb to FL230, squawk 5415"

This clearance is to enter the airway system - Manchester's airspace - but as Ronaldsway is in a Control Zone and may have its own inbound/outbound traffic you also need a Zone clearance. ATC tend not to issue two separate clearances as R/T time can be tight and so they will issue a single clearance for your flight.

If Ronaldsway has no conflicting traffic the clearance will be just the airways clearance above. If they need to keep you away from other local traffic they may impose a further height or heading restriction. This will make a difference to the manner in which you program the autopilot.

If you just get an airways clearance you can activate the FMS on take off.

If you get additional zone clearance instructions - an example being:

"JHB999 is cleared from EGNS to EGLL via L10, maintain FL230, squawk 5415. After departure turn right onto a heading of 180, not above 3000ft until instructed."

- then you should select the height and heading in the autopilot MCP. This is a derivation from your planned route but you should expect such clearances - and be aware that the first few minutes of flight may involve further height or heading instructions.

After take off and when the controller is happy you are clear of his traffic he will instruct you to "resume you own navigation to KELLY" at which point you can engage the FMS and set course for KELLY.

Think about this for a while as it may need you to revise your methods of flying in FS. Ensure you are happy with both basic autopilot flying on departure as well as engaging the FMS. If you are given initial headings to fly then make sure that when you engage FSNav or FMS you know it will take you from your present position to KELLY (or any point the controller has cleared you to - he may say "resume your own navigation direct to WAL"

Taxi

Going back to the real flight we now have the crew being given taxi instructions, writing these down and checking the route against the airfield plate. Once under way they start on the departure (pre take off) checklist, set up the navaids for the initial departure route, pause while the ATC clearance comes through and then complete the checklist. It's a busy time.

In FS we don't do half these things but if you are trying to be realistic (PMDG crews) do as the real crews do. Taxy out slowly. There's no prize for getting to the hold fast and it only overheats the brakes. Slow taxying can be tricky in FS but it can be done so give yourself a chance. 15kts is an ample speed.

Note: On some aircraft the navaids are set up in the FMS during cockpit initialisation checks. The navaids are all tuned in for the appropriate departure, the MCP is set to runway heading and altitude (assuming a SID departure here) and speed set to flaps up manoeuvring speed.

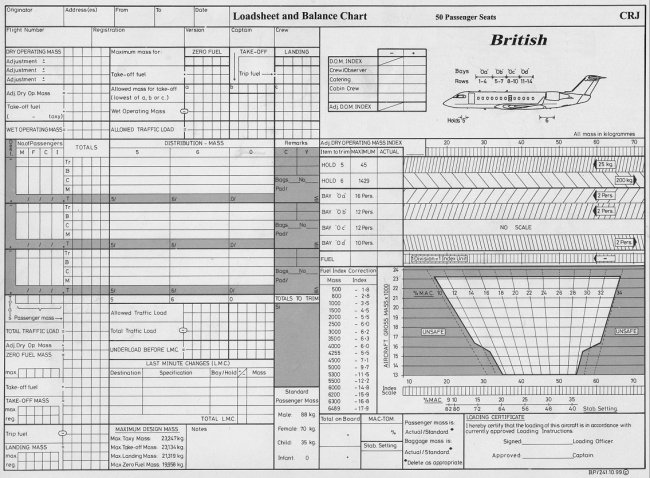

Whilst I am talking about settings I'll add something more here that is very important in real world aircraft that we tend to ignore in FS. During cockpit initialisation the crew will receive a load sheet from the dolly bird in Load Control. This gives the passenger, freight and fuel loading of the aircraft. This is a vital document in flight preparation as it also calculates the C of G for the aircraft. These values are fed into the FMS - the weights determine the take off and landing speeds and the C of G determines the very critical tailplane incidence angle.

Once at the hold most of the cockpit workload should be over and the crew will be waiting for take off clearance. When they get this the actual entry onto the runway is brisk - pilots don't hang around on the active.

Departure

After take off it gets busy. A normal sequence is gear up, speed at V2 +15, roll mode (if applicable) set at 400ft and then speed to flaps up manoeuvring speed above 1000ft. Autopilot is engaged at the minimum allowed altitude (it varies with aircraft).

If the ATC clearance does not contain an ATC heading restriction then, as we discussed above, the pilot will engage the FMC to turn the aircraft to KELLY and pick up the onward route. In other words the autopilot will be engaged in NAV mode right away. However, if ATC has issued a local restriction to the airways clearance the pilot will use the HDG and ALT selectors on the MCP for the first few minutes of flight.

Passing 3000ft the pilot will change altimeter setting to 1013.2mb.

Once clear of local traffic Ronaldsway can direct the aircraft to KELLY (or maybe WAL if Manchester are happy) - or may even ask the pilot to maintain a specific heading if Manchester have asked for one. The pilot will be directed to contact Centre immediately after.

Note: Approach will usually transfer you to Centre as soon as you are clear of local traffic. Your actual location is not relevant and you may still be well inside the Zone. Handovers are not fixed at the Zone Boundary but are done if the controller has no further conflicting traffic.

En Route

Switching over to Centre the pilot will report on track for KELLY (or repeat his radar heading) and climbing to his assigned airways level. Manchester will respond by confirming the cleared level or may (now the aircraft is on his radar) clear it higher - but only up to FL130 as that is their airspace limit.

Climbing through FL100 the pilot will adjust speed from 250kts to the aircraft's optimum climb speed.

After liaison with London the Manchester controller will (if the aircraft is clear of all his traffic) clear the pilot to climb to the level London has issued and ask the pilot to call London Centre.

On contacting London Centre they will again verify the level the pilot has been cleared to.

The remaining climb will be much lower on workload and will take the aircraft to just south of WAL VOR on track for HON VOR.

Although the FMS will have been engaged once the aircraft has been cleared on track this may not last for long on such a short flight. It is common for aircraft to be put on a radar heading a few minutes after leaving WAL VOR. Sometimes these headings will be continuous for the rest of the flight but ATC may also tell the aircraft to resume navigation some time later.

For FS pilots this may catch FMS users out as you will be changing from FMS to MCP mode - and then be required to re-engage the FMS for HON VOR. Make sure you know how to use the FMS in this manner - and also check you understand if the FMS will take you on a direct track to the beacon (which ATC may expect) or whether the FMS will try and re-establish the original planned track.

At some stage prior to descent the crew will discuss the approach. For FMC equipped aircraft this means selecting and verifying the planned arrival procedure, having checked the arrival ATIS for the latest runway data.

For non FMS aircraft it means finding the appropriate approach plates for the runway and talking these through so both pilots have a clear understanding of the procedure. This discussion will include details such as the heading and height to be followed leaving the holding pattern (although crews know full well that ATC will almost certainly be providing radar headings), any speed points, the approach aid and frequency, final inbound heading, Minimum Descent Height (MDH - for VOR/NDB approaches) or Decision Height (DH - for ILS approaches) and the Missed Approach procedure.

This approach briefing is just as valid in FS and I urge pilots to have a look through the approach procedure. Real pilots do it every day regardless of how many hundreds of times they have flown into the airfield (procedures do change) so it is not a bad habit to get into yourself. Even if you don't scan through the document (or do but can't memorise the details) make sure you know where various items are so that you can find them quickly if you need to.

At some point during the cruise the pilot will call company operations and inform them of the ETA at destination, predicted fuel burn and if there are any unserviceabilities.

Initial Descent

As the aircraft approaches HON VOR the pilot will probably get initial descent instructions from ATC. One of the first tasks they will initiate on descent is to check their landing weight (take off weight minus calculated fuel burn) and write the landing speeds on the placard.

Approaching FL100 speed will be reset to 250kts. ATC will be very quick to respond if they don't see any speed reduction on radar! Also passing this level the crew will run through the Descent/Approach checklist.

As the aircraft approaches WCO NDB the crew hit the SLP (Speed Limitation Point) for the BNN3A STAR. This is 250kts and so, regardless of the aircraft's actual level at WCO (above FL100 or not) it HAS to slow down to this speed. Passing WCO the crew turn towards BNN VOR and, hopefully, are cleared to FL70. This is the minimum stack level and it would indicate the aircraft would have no onward delay. If cleared to BNN at a higher level it would indicate traffic below and an almost certain entry into the holding pattern awaiting further descent.

Holding

BNN is the holding facility for Heathrow so any delays would involve flying a holding pattern here whilst the aircraft is stepped down to FL70. It is rare that you would get a hold in FS but don't assume this will never happen. Check the pattern's holding axis and make sure you can actually fly a hold. If you've not done one before then have a practise - it's not difficult.

The BNN holding pattern is also the second SLP for the approach and all aircraft at BNN should be flying at 220kts maximum - whether going into the hold or going straight into the approach procedure on reaching the beacon. 220kts means initial flap extension for many aircraft so check your flap speeds.

Final Approach

Heathrow Approach will ask the aircraft to leave BNN on a radar heading and descent to final approach altitude. For 27L this will usually be HDG 130 and height 2500ft QNH. The crew will check that all navaids are tuned and set to final approach course, altimeters are reset to QNH and DH is set on the bug. ATC will also ask the the crew to reduce to 180kts.

After approximately 13nm ATC will turn the aircraft right onto 240 to intercept the ILS. Flap is lowered to achieve the initial approach speed (or sometimes 160kts from ATC). As the localiser is captured the crew confirm correct capture and check heading against FAT. On glidepath capture speed is reset for the approach, flaps and gear checked and the approach checklist completed.

If the weather is bad with visibility or cloud near to minimums the approach will be flown down to Decision Height. This is a company minima based on the ILS equipment fitted to the aircraft and on the ground. Heathrow has full Cat IIIc autoland so, if the aircraft is suitably equipped a landing can be made in zero/zero weather. Not all aircraft have full autoland capability and if they don't the flight cannot continue below the DH unless the crew see the runway or approach lighting.

Missed Approach

A missed approach or go around can happen for several reasons and is more common than you may think. Obviously one factor is not seeing the runway at DH at which point a missed approach is mandatory. Other reasons may be an unstable ILS signal, aircraft incorrectly configured for landing, ATC directive, accidental runway incursion or failure of ILS equipment (aircraft or ground).

If a missed approach is necessary then the aircraft will inform ATC and commence the published MAP procedure. In the case of 27L this is to climb ahead to 1500ft, turn right onto a heading of 320 and continue climb to 3000ft. ATC may issue alternative instructions in which case the MAP is ignored.

The essential action in the go around is to ensure the aircraft is established in the climb as soon as possible because there is precious little vertical clearance at DH. In big aircraft the TOGA button is pressed and flaps raised to 15. Autopilot is monitored and attitude is checked to see if the aircraft has rotated to correct climb attitude. Once a positive rate of climb is observed the gear will be retracted and then normal after take off checks completed.

In FS, if you are not able to perform the take off checks from memory it is worth having the checklist handy during the approach just in case. Your desk may be a bit cluttered with paper (Approach plate, airfield diagram, landing checklist etc.) but it is better to have the paperwork nearby and ready to grab rather than freeze up if a go around is issued <g>.

After Landing

Once on the ground it will get busy again. Thrust is reduced to idle, and the crew check that autopilot is disengaged, autothrottle confirmed disengaged, speed brake is checked up and autobrakes are operating. With these confirmed reverse thrust can be applied.

When the aircraft reaches taxi speed the aircraft will vacate the runway as directed by ATC. Once clear of the runway frequency will be switched to Ground (if applicable) and the aircraft will be directed to stand. During the taxi in the after landing checks will be completed.

When on stand the shut down checks will be completed. Time for a cuppa..

Flight Analysis

I hope you found the article interesting rather than frightening. What I am hoping to show here is that real pilots have a wealth of information available to them which FS users may not. This is in the form of both written documents in the aircraft (check lists, abnormal check lists, approach and airfield plates) and a lot of information already in the pilot's minds from years of training and experience.

As FS users start on the road towards higher realism the tendency is to first get an aircraft with very accurate real world systems - the PMDG 737 being a very good example. It can take a lot of time to settle down with this aircraft as the system complexities, especially the FMS, need time to learn. In truth you are learning to use a very accurate mimic of the real world systems and, without enforced classroom training to hammer the systems into your brain, it will take some time to learn them all. It will be darned good fun but it is also going to demand some work from you to understand it all.

Whilst you can learn the intricacies of the aircraft systems quite well the background operations to airline flying are not so readily available. In truth there are some gaps that make life difficult for FS pilots. For example few flight planners are capable of calculating en route times with current weather conditions so flight time (and fuel burn) can't be accurately determined. Many aircraft have no means of calculating take off or landing weights and therefore the correct speeds. It is this lack of planning data that can make flights in FS difficult.

In essence we learn by experience and online ATC tends to push the learning curve at you faster than you may think. Flying the PMDG 737 or similar in an online, real time ATC environment is going to be tough and a target you can be proud of if you can meet the challenge.

The real test is not in the everyday flights that flow along as you expect but when ATC or other factors throw something at you that you are unprepared for. In the real world flying is a continual process of changing factors and it is the crews experience that turn these from the unusual to the commonplace. This is what you will have to develop in FS so that if something unexpected does happen you are not fazed by it. Paradoxically, the more you develop skills to handle the unusual the less often you will find yourself in unusual situations..

The bottom line is experience. The more you fly the more you will learn. In the meantime just enjoy the experience and if something unusual does crop up dig out the docs or grab a pilot and ask about it.

One more thought..

When did you last practise:

A

hold,

a missed approach,

a VOR approach,

a bad weather approach,

a diversion to alternate,

any sort of engine/instrument/navaid failure,

an autopilot failure (flying an ILS manually) or

any combination of these?

Real crews undergo base checks at regular intervals and FS users should never consider they are "beyond training". If you have an hour why not flog over to the nearest beacon to try a hold or two - or see how you get on with flying an ILS manually? It certainly will not be time wasted.